Opera Explained: Recitative

Opera Explained: Recitative

By Isaiah Feken, Opera Colorado Baritone Artist in Residence

As an opera singer, I believe I should act as an ambassador, or as I often joke, a proselytizer for the genre. Over the years I have found that many potential opera lovers find opera to be intimidating and complicated. While it is rich with complexities for those who enjoy them, at its core, opera is storytelling and a powerful medium for capturing the human condition. By understanding some of the underlying structures and devices used to organize opera, listeners can break down, understand, and hopefully fall in love with the genre.

I have found that an important first step in understanding and identifying many structures within opera is recognizing the difference between recitative and “numbers,” i.e. arias (solos), duets, and other ensembles. Being able to identify recitative can help opera listeners understand how operas are put together and even understand how the genre has developed over time.

What is recitative?

As the name would suggest, recitative is closely related to recitation or speech. While recitative can lengthen and stretch language slightly for dramatic effect, the defining characteristic of recitative is that it follows speech rhythm. In order to do this, certain forms of recitative, such as secco recitative, do not have strict regular beat, or pulse. The singer delivers the words on pitch and the continuo or keyboard player changes the chords accordingly. This is perhaps the closest opera and straight plays ever come to intersecting, as the singer has near total control over the pacing and phrasing of the text.

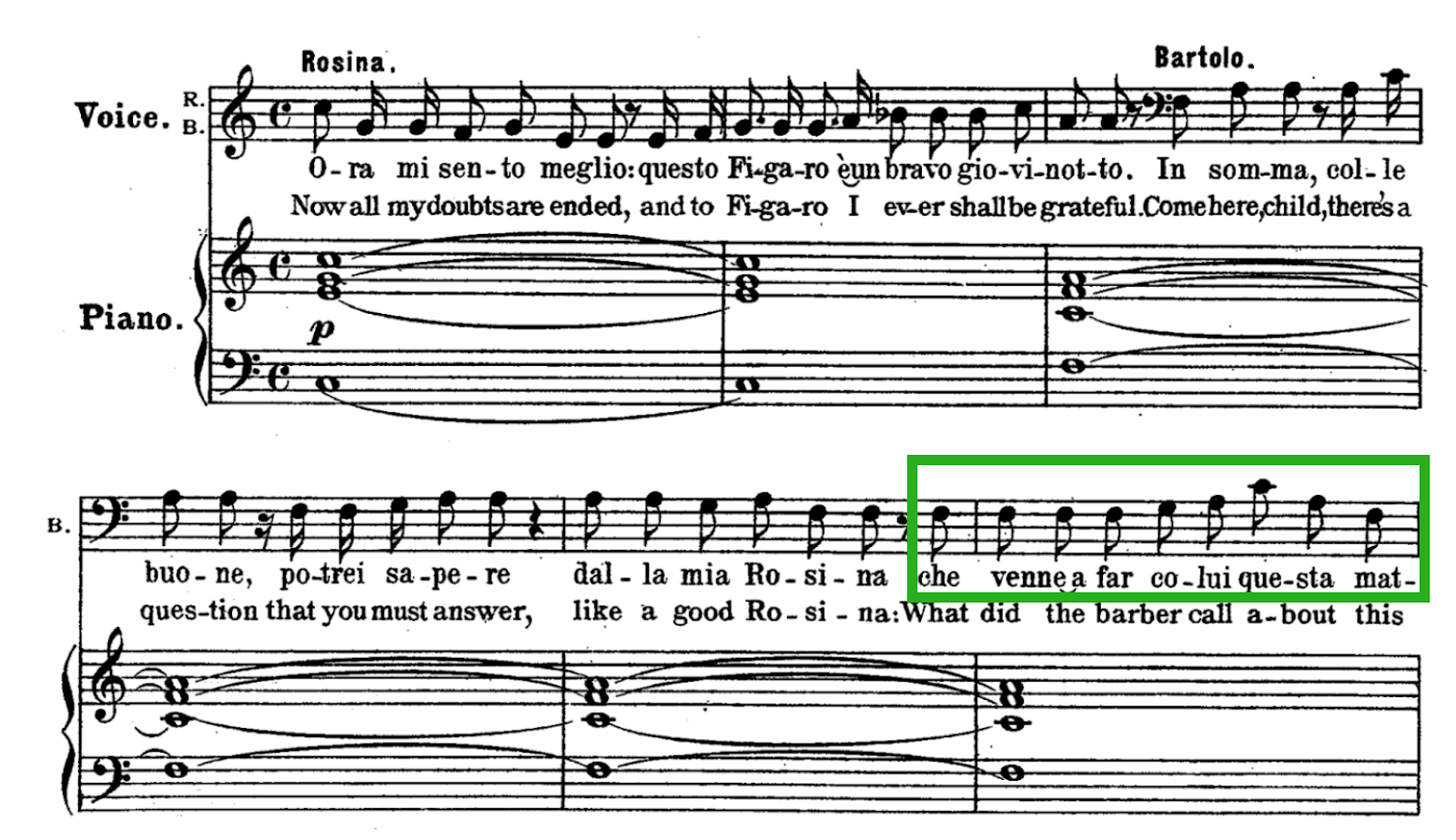

In this example of secco, or dry recitative from Il barbiere di Siviglia, sung by Opera Colorado favorite Mr. Stefano DePeppo, listen to how Mr. DePeppo slows down and almost pauses towards the end of the phrase, marked by the green box.

Stefano de Peppo sings “In somma, colle buone” from Il barbiere di Siviglia

This high level of sensitivity towards text and dramatic intent is what defines recitative. Of course, not all recitative is secco. As the orchestra becomes more involved, the line between recitative and “numbers” becomes progressively ambiguous.

When a recitative includes the orchestra it becomes recitativo accompangato, or accompanied recitative. With the addition of the orchestra, coordination between singer, conductor, and orchestra becomes much more important. Unlike secco recitative, every recitativo accompagnato has a specific tempo and a regular meter (specific number of beats per measure). In order for speech rhythm to continue to play its important role with these new constraints, some clever writing techniques are used for the orchestra. As an example, in recitativo accompagnato the singer and orchestra will often trade small phrases, allowing the singer to take slightly more or less time without negatively affecting ensemble cohesion.

Listen to these two different performances of “Hai gia vinta la causa” from Le nozze di Figaro. Notice how each singer delivers the text slightly differently.

Rodney Gilfry sings “Hai gia vinta la causa” from Le nozze di Figaro

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sings “Hai gia vinta la causa” from Le nozze di Figaro

How to Identify Recitative

As opera developed, accompanied recitatives became more and more substantial with greater interplay and balance between the singer and orchestra. By the time of Verdi’s La traviata and Rigoletto, recitative and arias were beginning to blend more and more to the point where entire selections defied easy classification.

Listen to this selection from Verdi’s Rigoletto. Try and identify where the recitative ends and the aria begins. If you can, try snapping or tapping your foot along to a pulse if you feel one, and see how long that regular pulse lasts.

Cornell MacNeil singing “Pari siamo” from Rigoletto

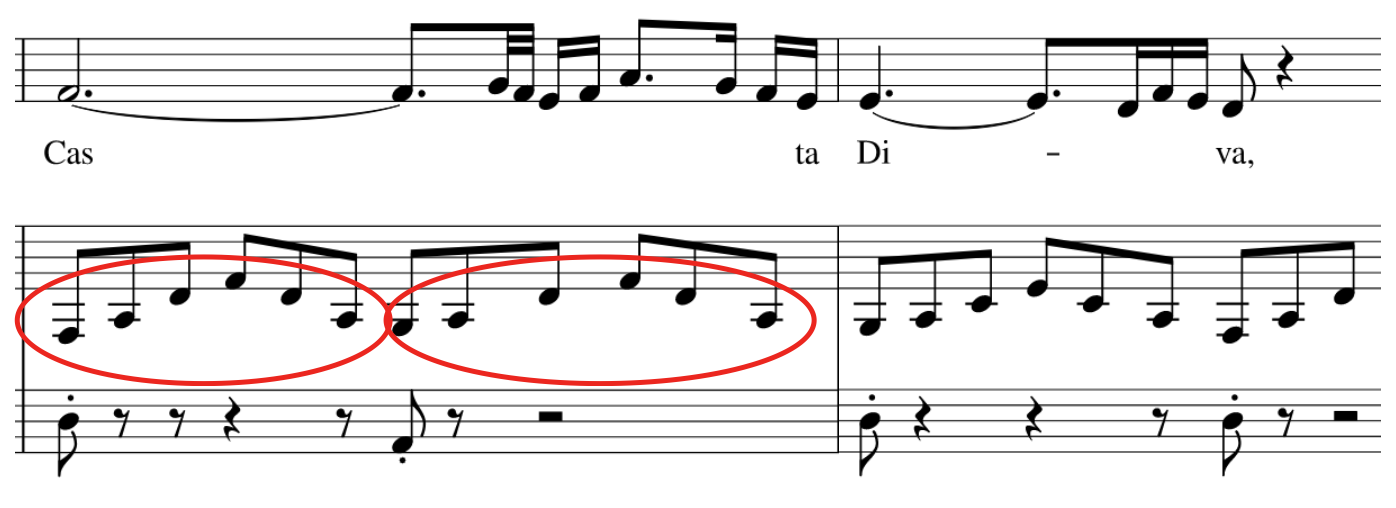

How do we navigate these murky waters? Here is an easy method to help you differentiate between recitatives and arias or other “numbers:” think R&R, or rhythm and repetition. The rhythm in R&R refers to speech rhythm, because, as we said before, recitative tends to follow speech rhythms. Arias and other numbers, conversely, tend to elongate words beyond normal speech to facilitate sustained melodies. A great example of this is the famous “Casta diva” from Bellini’s Norma. If you hear a singer sing a series of long or sustained notes, chances are you are not in a recitative. Looking ahead, notice the repeating pattern in the accompaniment used to support the singer.

Leontyne Price sings “Casta diva” from Norma

Next is repetition, not the repetition of words, but of certain patterns within the orchestra in order to create a regular pulse (think of the snapping, tapping exercise from earlier). These repeating patterns or figures help establish that regular pulse and, along with the conductor, help to keep the ensemble together. These figures or patterns can happen in recitative, but are never sustained for very long.

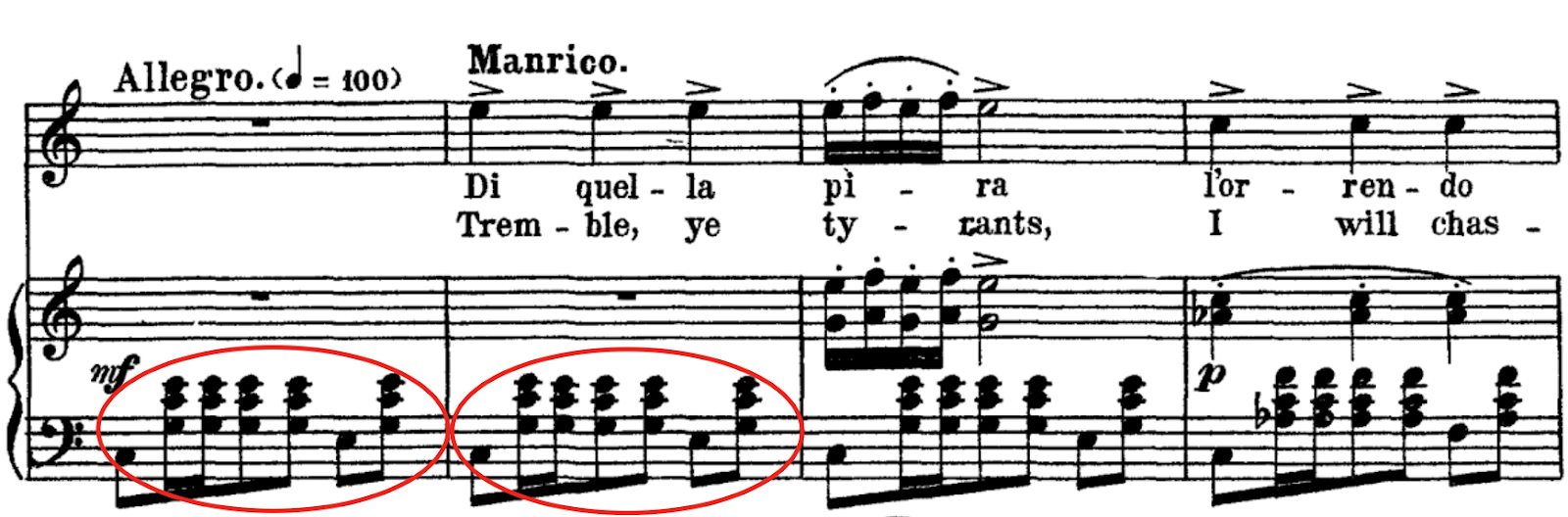

There are several “standard” repeating patterns used in opera. I am particularly fond of the high-energy patterns associated with cabalettas: fast finales to multi-section arias popular during the early to mid 19th century. One of my favorite cabalettas is “Di Quella” from Verdi’s Il trovatore.

Franco Corelli sings “Di quella pira” from Il Trovatore

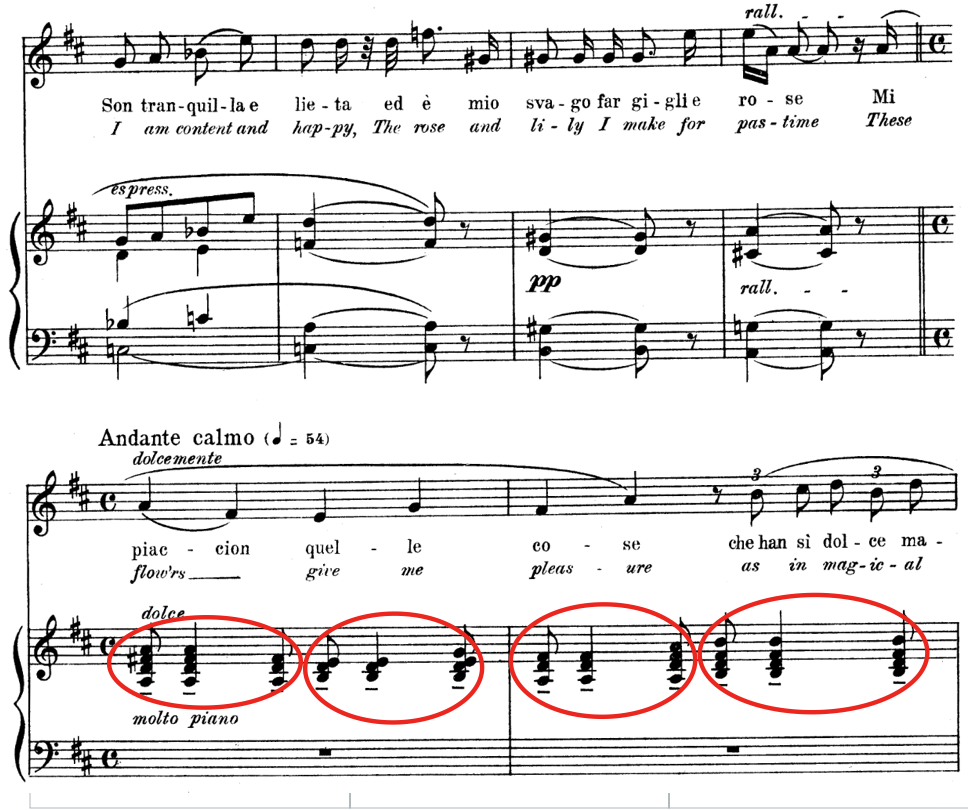

If you listen hard enough, you can find repeating patterns in even the most through-composed operas, like in the excerpt below from “Si, mi chiamano Mimi,” from Puccini’s La boheme. Composers such as Wagner, Puccini, and Richard Strauss relied more on themes and leitmotifs to help structure their works than the recitative and numbers format, but traces of the old system can still be found in even the most avant-garde operas.

Mirelli Freni sings “Si, mi chiamano Mimi” from La boheme

Hopefully, by understanding what recitative is and how to listen for it, you can navigate the—sometimes intimidating—waters of opera. The genre has so much to offer, and anyone can learn to love it.

If you want to continue learning about recitative, I highly suggest this video of Bernstein, demonstrating the recitative styles of famous composers while discussing the high price of chicken.

Leonard Bernstein: What is recitative

Additional Reading:

- Elliott, Martha. Singing in Style: A Guide to Vocal Performance Practices. United Kingdom: Yale University Press, 2006

- Gossett, Philip. Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Hoch, Matthew. A Dictionary for the Modern Singer. United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014

- Miller, Richard. On the Art of Singing. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1996

- Kimbell, David R. B.. Verdi in the Age of Italian Romanticism. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1985: 323-325

- Montgomery, Alan. Opera Coaching. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2007

Great job Isaiah