Meet the Composer: Erich Korngold

By: Bethany Wood and Angelica DiIorio

Meet the Hollywood score composer and incredible talent responsible for our winter production of Die tote Stadt (The Dead City): Erich Korngold. Korngold composed the opera in 1920 and worked on the libretto with his father Julius. Let’s learn more about the work of this composer who showed great promise from an early age.

Korngold And His Family

Source: Longborough Festival Opera

The careers of Julius Korngold and his son Erich are intertwined. Both father and son were born in Brünn, a city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Brno in the Czech Republic). Both spent their lives pursuing music, Julius as critic and Erich as composer.

In 1902, the family moved to Vienna, the music capital of the time. The influential paper Die Neue Freie Presse invited Julius to join their staff. The paper championed traditional styles of music, a cause Julius promoted throughout his lifetime. In 1904, Julius headed the paper’s music editorials, becoming the most powerful and feared critic in Vienna.

Korngold: A Child Prodgy

Source: Museum of Music History

Through his father, Erich grew up among the world’s musical elites. As a child, he was taken to watch Gustav Mahler conduct rehearsals at the Vienna Hofoper (the city’s opera house). From an early age, Erich demonstrated a talent for music. He began beating time with a kitchen spoon at the age of three, playing piano at four, and writing music at six.

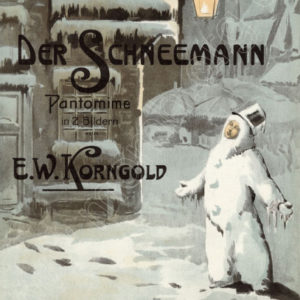

Julius suspected his son of genius but worried he might be deluded by parental bias. Accordingly, Julius showed Erich’s compositions to Mahler, who declared “A genius! A genius!” and recommended Erich study with composer Alexander von Zemlinsky. Erich flourished under Zemlinsky’s tutelage and, by age eleven, had composed a ballet, Der Schneemann (The Snowman). The ballet premiered at the Vienna Hofoper in 1910. The composer was then thirteen.

Everyone’s A Critic

As a powerful critic, Julius had made many enemies in the music world, and several criticized young Erich as a result. They claimed Julius was the true composer of Erich’s works. They even accused Erich’s parents of recently adding “Wolfgang” to his name to position their son as a genius. Despite this, Erich soon gained a following. According to one historian, “not since Mozart had a child prodigy so riveted Vienna.” Erich and his father began traveling across Europe, attending performances of his works in various cities, including Prague and Berlin.

Die tote Stadt’s Beginnings

Source: White Studio, from the MET archives

In 1916, playwright Siegfried Trebitsch suggested Erich adapt Georges Rodenbach’s play Le Miarge, itself an adaptation of Rodenbach’s symbolist novel Bruges-la-Morte, into an opera. After reading Trebitsch’s German translation of the play, Erich drafted a scenario, which he and his father turned into a libretto. Worried Julius’s involvement would invite accusations of favoritism, the father and son team authored the libretto under the penname “Paul Schott.” Their ruse was so successful, the secret remained within the Korngold family until 1975.

The turmoil of World War I interrupted work on the opera. Erich served as musical director for an infantry regiment during the war. He composed pieces to raise money for the Austrian War Relief Fund. After the war, Erich returned to adapting Rodenbach’s play. By this time, he was so well known, theatres vied for the premiere, and Die tote Stadt obtained a rare double-debut, opening December 4, 1920 in both Cologne and Hamburg.

Rising Anti-Semitism

The Korngolds, including Erich’s wife, Luzi von Sonnenthal, were Jewish in a time when anti-Semitic prejudices were rising. In Germany, the new Nazi government began replacing Jews and their sympathizers with musicians who agreed with the regime’s racist ideology. The German government forbid Jews from teaching music, and in 1933, the they banned music by Jewish composers, including Korngold. Despite these developments, Erich and his family, like most of Europe’s population, believed such outrages would be contained.

Korngold in Hollywood

In 1934, Erich and his wife began traveling regularly to Hollywood, where Erich had been hired to score several films. In 1937, they returned again to Vienna where they remained through the new year so they could attend Die Kathrin, Erich’s opera, which was scheduled to premiere in the new year. Wary of increasing aggression from Nazi Germany, the couple decided to accept an offer from Warner Brothers for Erich to score their film Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havailland.

Listen to the music from Robin Hood below and get a preview of the music in Die tote Stadt on our blog>>

A Narrow Escape

The Korngolds sailed for the States on January 29, 1938 so Erich could work on Robin Hood. They were convinced Austria would never allow the evils rumored to be happening in Germany, so they left their oldest son Ernst with relatives so his schooling would not be interrupted.

Hitler entered Austria on March 12, 1938. Korngold and his wife were still in Hollywood. Julius had obtained a visa to flee with his wife and grandson on the last unrestricted train out of Austria. The family soon reunited in California, where they spent the remainder of the war supported by Erich’s work writing film scores.

Korngold’s Legacy

Source: The Korngold Society

Throughout his time in Hollywood, Erich composed music for over twenty films. He earned two Academy Awards and revolutionized music in cinema. As biographer Jessica Duchen explains, “instead of scribbling ‘wall-to-wall’ atmospheric accompaniment, Korngold showed how music could be woven integrally into the structure of a film; he not only raised the quality of the music but also its relevance to the movie as a whole.”

After the war, Korngold’s Romantic style no longer appealed in a world of modern, atonal composition. Korngold died in 1957 from a cerebral hemorrhage. After his death, Korngold’s music went largely unperformed until the 1970s, when a renewed interest in composers suppressed by the Nazis prompted recordings and performances of his work. Today, he is widely recognized as one of the great composers of his day and Die tote Stadt one of his crowning triumphs.

—

Bibliography

Carroll, Brendan G. The Last Prodigy: A Biography of Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1997.

Duchen, Jessica. Erich Wolfgang Korngold. London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1996.

Goldmark, Daniel and Kevin C. Karnes. Eds. Korngold and His World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Hass, Michael. Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis. New Haven; Yale University Press, 2013.

Horowitz, Joseph. Artists in Exile: How Refugees from Twentieth-Century War and Revolution Transformed American Performing Arts. New York: Harper Collins, 2008.

Thank you, Opera Colorado, for preparing these notes and the music from Robin Hood. I have never seen “Die Tote Stadt” and this material is very informative for those planning to see it at Opera Colorado.