Turandot 101: Program Notes

By: Betsy Schwarm

Turandot stands last in the catalog of its composer, Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924). Last because he did not live to complete it. He was at work upon the score when health problems developed and were ultimately diagnosed as throat cancer. An experimental treatment might have saved him, had Puccini not suffered a fatal heart attack after the procedure. In his luggage at the hospital was the manuscript of Turandot, still a few scenes short of completion.

Learn more about Puccini’s Turandot and get your tickets before its sold out>>

Who creates and finishes Turandot?

After Puccini’s funeral, attention turned to the fate of Turandot. The great maestro Arturo Toscanini (1867 – 1957), already scheduled to conduct Turandot’s premiere, wanted Italian composer Riccardo Zandonai (1883 – 1944) to complete it. However, Puccini’s adult son Tonio judged Zandonai to be too well known and too likely to make the piece more his own than Puccini’s. Viennese operetta composer Franz Lehar (1870 – 1948), who had been a close friend of Puccini, was similarly rejected. Tonio preferred Neapolitan composer Franco Alfano (1875-1954), a composer of moderate talent and limited success. Here, the younger Puccini felt, was a man who would not attempt to place his own mark upon the master’s music but would instead be willing to continue in the original spirit.

The task was daunting, for who can match the genius of Puccini? Alfano began with Puccini’s incomplete sketches of the final scenes, which he extended by working in themes from earlier in the opera, principally borrowing from the tenor’s showcase aria “Nessun dorma,” which opens act three. Alfano did his best work, producing the finest music he would ever compose.

A Dramatic Opening

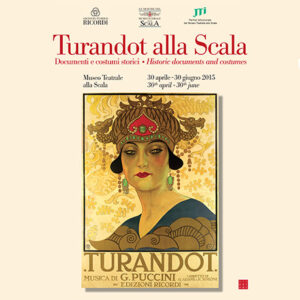

Nonetheless, at the opera’s premiere at La Scala on April 25, 1926, Toscanini stopped the performance at the moment of the last chord from Puccini’s pen. A Milan review of the event reported, “Then, from where he stood as conductor, Toscanini announced in a low voice full of emotion that at that point Puccini had left the composition of the opera. And the curtain was slowly lowered on Turandot.” Only in subsequent performances was Alfano’s contribution heard, bringing Turandot at last to dramatic and musical resolution.

Turandot’s Origins

The opera tells a tale derived from the stage drama Turandot (1762) by Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi (1720 – 1806). Gozzi’s tale of a Chinese princess, murderously dispensing with would-be suitors because of an ancient grudge, had been given musical treatment numerous times. Yet librettists Renato Simoni and Giuseppe Adami asked Puccini to join them in a new setting. Simoni and Adami would provide words and scene structure. Puccini would be responsible for giving musical expression to the scenes and passions.

Musical Themes in Turandot

Each of the three acts features an aria spotlighting one of the three major characters. In act one, devoted servant Liù has the tender “Signore, ascolta.” It is music with a tear in the eye, bringing home to listeners the challenges she has endured. By contrast, there are few tears and no wistfulness in act two’s “In questa reggia,” as Princess Turandot establishes herself as assertive and aggrieved. Any sorrow she feels is soon overcome by outrage.

Act three contains what is not only the most famous aria in Turandot, but possibly the mostly immediately familiar aria in all of opera. Calàf’s “Nessun dorma” is at first reflective as he considers the perilous situation in which he has placed himself. Ultimately, it all builds to a three-fold declaration of expected triumph: “Vincerò! Vincerò! Vincerò!” With heroic horns joining him for each statement, one cannot help but to be firmly on Calàf’s side.

Offsetting those three central characters is another set of three: court ministers Ping, Pang, and Pong. Their frequent banter provides a touch of comic relief, as well as a down-to-earth perspective as they try to cope with the demands of their work. Funeral planning is, for them, just another day on the job.

The Work of Fairytales

Is it a historically accurate view of ancient China? No: wholly fiction—a rather dark fairytale—and in fairytales, historical accuracy is not a principal issue. After all, do bloodthirsty witches lurk in gingerbread cottages in the Black Forest? Surely not, though that does not undermine the magic of Humperdinck’s 1893 opera Hansel und Gretel.

Bringing her own vision to Opera Colorado’s production, director Aria Umezawa is adding a brief prelude and postlude, placing the tale in a clearer context. The intention is to enrich the audience’s experience without distracting from the music itself. Turandot, it seems, can still speak to us today.

Learn more from Aria Umezawa’s Director’s Notes on Turandot>>

—

Program note by Betsy Schwarm, author of the Classical Music Insights series.